Strength in Numbers

IN A YEAR WITHOUT LODGE, CALIFORNIA FREEMASONS

MADE THEIR PRESENCE FELT LIKE NEVER BEFORE.

By Ian A. Stewart

Last Spring as COVID-19 wreaked havoc across the country, Darin Sanden resolved to do whatever he could for his lodge brothers, many of whom found themselves out of work and struggling financially. Sanden, master of Yucca Valley No. 802, near Joshua Tree, started looking for things he needed done around the house: moving furniture, clearing out the garage, that sort of thing. “It was $50, $100,” he says. “Some of these young guys, they’re gig workers. I was just trying to help out.”

Sanden was doing what generations of Masons before him have done in times of crisis: offering relief. As an obligation that Master Masons take on, that part came naturally. What didn’t, was asking for help when he himself needed it.

In late summer, Sanden lost his job as a hearing-aid technician. His wife, a home health professional, was out of work, too. The couple scrambled for whatever work they could find. They applied for unemployment and CalFresh benefits. “We made it stretch as far as we could,” Sandin says, but money was still tight. His lodge brothers suggested he turn to Masonic Outreach Services (MOS) for help. “I never imagined I’d be the guy on that side of the table,” Sandin says. Reluctantly, he agreed. What he saw there, he says, forever changed his view of Freemasonry.

A BROTHERHOOD TRANSFORMED

The pandemic has affected just about every aspect of the fraternity over the past year. In March, lodges suspended in-person meetings and activities, instead relying on Zoom meetings to stay in touch and conduct essential business. Members around the state organized food drives, arranged grocery and medication delivery for the elderly, and reached out to members’ widows and other vulnerable folks. At the Masonic Homes in Union City and Covina, campuses were closed to visitors and public spaces made unavailable; practically overnight, management rushed to develop protocols to keep residents and staff safe.

Every branch of the organization adapted: At the Masonic Center for Youth and Families, counselors shifted to tele- and videoconferencing, and began offering emotional-wellness “virtual visit” calls free of charge to residents and staff at the Masonic Homes. The Acacia Creek Retirement Community joined with the Union City campus of the Masonic Homes in expanding the programming available to residents, who were otherwise cooped up in their apartments. Perhaps no example of this was more dramatic than, in April, opera soprano Tracy Cox singing “America the Beautiful” as flag-waving residents watched from their balconies. On social media, a video of the performance was viewed nearly 50,000 times.

Life on these campuses was indeed transformed by COVID-19—but rather than wall residents off entirely, staff at both Acacia Creek and the Masonic Homes doubled down on opportunities for safe socialization and companionship. These included activities like hallway happy hours, grocery and goodie delivery, balcony workouts, car parades, grab-and-go cocktail hours, and library pickup service. At Acacia Creek, leaders developed a myriad of virtual programming for residents and staff, including online exercise programs; video-conferenced Great Courses, discussion groups, and TED Talks; online film nights; Zoom and other web-tools tutorials; even a dinner-theater reading.

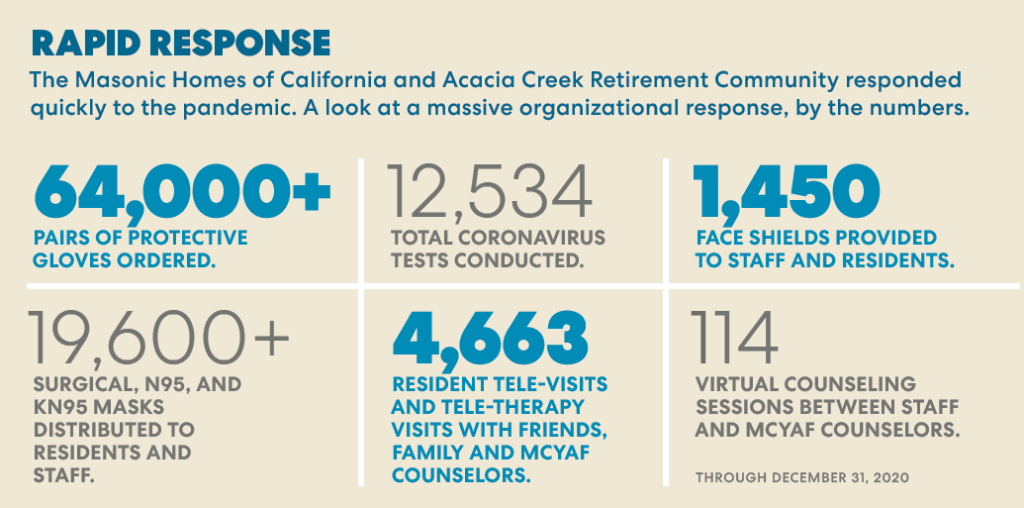

Ensuring the health and safety of everyone was paramount. Campus managers rapidly developed new safety standards, including administering more than 11,000 coronavirus tests to staff and residents through mid-December. The Masonic Homes also recruited heavily, hiring 78 additional employees to help manage the load.

DISTRESSED WORTHY BROTHERS

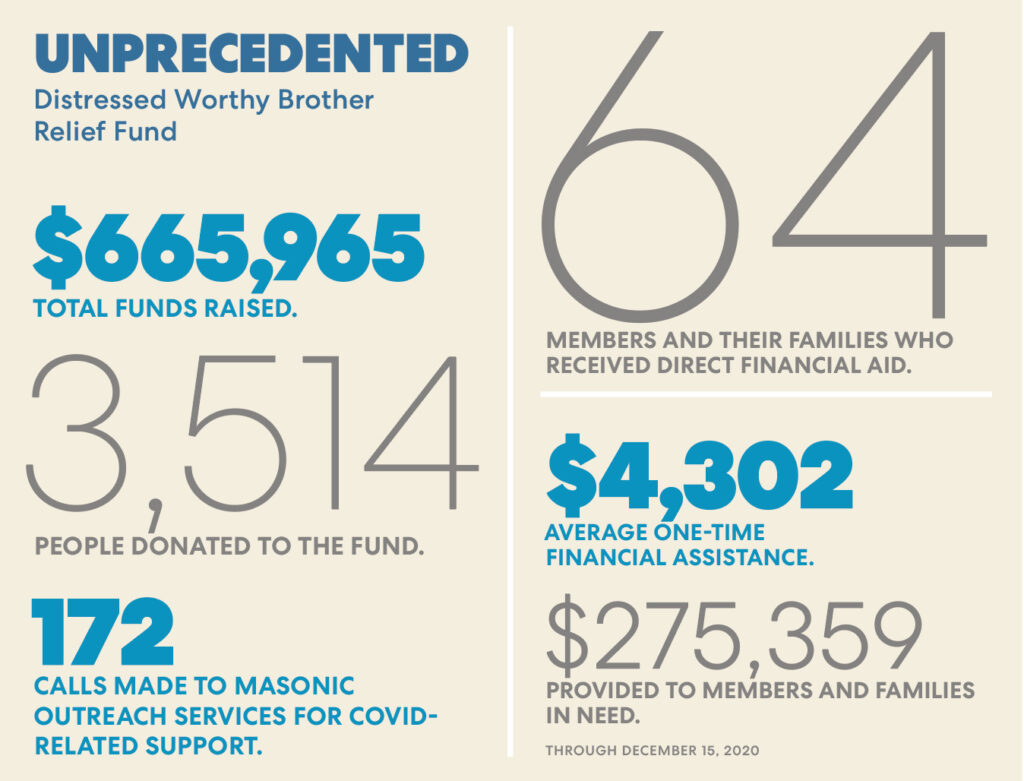

During those hectic first weeks of sheltering in place, fraternity leaders began working behind the scenes on an organization-wide response to what was clearly a burgeoning crisis. The result was the formation of the Distressed Worthy Brother Relief Fund, an emergency charity drive. Administered by Masonic Outreach Services (a division of the Masonic Homes of California), organized by the California Masonic Foundation and the Grand Lodge, and powered by donations from individual members and lodges, the fund brought every part of the organization together to provide services and financial support to Masons affected by COVID-19. Charity from the new fund would be expanded to help all members, regardless of age, degree, or lodge affiliation.

The response was overwhelming. The first $5,000 was raised in 20 minutes. Within a week, the fund had reached more than $30,000. One month in, Masons had donated $221,000 to the effort. By the end of the fall, fundraising records had been smashed, with more than $650,000 for COVID relief and overall Annual Fund giving above $2 million for the year, a new high-water mark.

Beyond the dollar amounts, the Distressed Worthy Brother fund clearly resonated with California Masons—even those who’d never given to the Foundation before. Twice as many members made their first charitable gift in 2020 as in 2019, the most first-time donors in nearly 20 years. “This is Masonry in action,” says Sabrina Montes, executive director of Masonic Outreach Services. “It’s activating a safety net that Masons have created over hundreds of years. It shows how powerful the tenets of Masonry are.”

For members like Jack Wolf, a member of Hollywood No. 355, the call for relief served as an opportunity to put his Masonic values into practice. Wolf, 88, understood the value of Masonic support firsthand: The previous fall, his wife had passed away. A month later, his dog died. “A lonely period for me,” he says. It left a powerful impression weeks later when a lodge brother called to check in and make sure he was doing OK. “I felt a warm, secure feeling in my heart that I had help if I needed it.” When the opportunity to pay it forward presented itself, Wolf did just that, signing over his $400 government-issued stimulus check to the fund. “It puts another warm feeling in my heart that I was able to help a brother in need,” he says.

Clearly, the need was great: Right away, MOS began receiving calls from Masons who’d found themselves out of work. Care managers compiled information about local, state, and federal services available to those in need. They also consulted with members about their finances and advised them regarding bill forgiveness and payment options offered by many companies. “The MOS team is made up of social workers,” Montes says. “We know how to provide care-management support, which often is what people really need. We wanted to serve as a sounding board to members in crisis, to help them find a path out of this.”

Crucially, MOS was also equipped with the infrastructure to quickly wire funds to those in need, often within a week. The team developed an abbreviated application that reduced the burden of paperwork and sped the process along. In many cases, the quick injection of aid helped members bridge the gap until unemployment benefits or other financial help arrived. Assistance ranged widely depending on need, averaging $4,302 per member or family. Not a life-changing amount of money, “but it is lifesaving at a time when there’s no other support out there,” Montes says. With the state unemployment system inundated by requests, “what we helped ensure was that every person was able to keep a roof over their heads and food on their plates until other benefits became available,” she says.

HELP ON THE WAY

For Sanden, turning to MOS was a humbling experience, but also a rewarding one. For years he and others had stressed to new members the importance of providing aid to those in need, little expecting he’d be on the receiving end. (In fact, in the spring, he made a modest donation to the fund himself.)

Sanden was quickly connected to a care manager who reviewed his finances and pointed out programs and services in his area such as hiring lists, food banks, assistance filing for unemployment, and working with lenders to defer payment.

In the end, Sanden determined that what he needed most was help paying for a hearing-aid certification exam he would need to pass in order to be hired by another company in his field. The test was given in person, in Sacramento, which meant he needed funds for the exam fee, air travel, and lodging. The money was in his account within days. “It was a huge help,” Sanden says. “It showed that we’re not giving handouts— we’re giving a hand up.”

In the following weeks, Sanden’s care manager continued to check in to make sure he was OK and to keep him apprised of other services. Sanden’s unemployment benefits were eventually approved, providing a measure of stability. But knowing that someone from MOS was there to help was an enormous emotional relief, he says. “I can’t even tell you how much faith I have in our organization because of this,” he says. “All the messages I get, the personal phone calls—these folks are the best there are.”

Unfortunately, the need for help—for Sanden and so many others—didn’t end there. By winter, as case counts mounted again across California, MOS was bracing for another round of calls for aid. And though the Masonic Homes and Acacia Creek were on track to have all residents and staff vaccinated by January 2021, for many, the fallout is ongoing. Lost jobs, missed wages, deferred bills—the impact of the crisis is far from over. For Sanden, that reality is clear: In December, his unemployment benefits were set to expire, and despite passing his exam, he’d yet to land a job. “We’ve been hanging on by the skin of our teeth,” he says. “Obviously, we’ll try whatever we can. But in our area, in rural San Bernardino County, there aren’t a lot of options. We’ll do our best to survive.”

A LASTING LEGACY

Recognizing that the need for help remains, the California Masonic Foundation has announced that the Distressed Worthy Brother program will continue into the new year as part of the 2021 Annual Fund. Rather than solely provide COVID relief, it will serve as an emergency fund for Masons going through all manner of crises. In a state continually dealing with the specter of natural disaster and faced with the uncertain prospect of a post-pandemic economic recovery, it’s likely that Masons will again feel the need to tap into the reserve. “This program will live on beyond the pandemic,” Montes says.

For Masons like Sanden, that’s a reminder—of the obligation to help and, as he experienced, of the importance of asking for it.

Sanden says that when prospects approach his lodge, coaches talk to them about the importance of contributing to charity—and also about being big enough to ask for help when it’s needed. “It’s humbling, but that’s what balances you out as a person,” he says. “It’s OK to turn to another brother and say I need your help. What good would we be as a fraternity if we let you fall?”

The experience, he says, has offered him an entirely new perspective on Masonry.

“How do we continue to go forward—to get up every day and work toward the bright future ahead?” he says. “We keep reinventing ourselves, carving the stone. I can’t tell you, I’m so thankful. They’ve got a Freemason for life—and one who will one day be in a position to be charitable to someone else.”

Read More From the Annual Report

Table of Contents

Nurses in PPE caring for residents in the Lorber skilled nursing environment at the Masonic Homes of California in Union City.