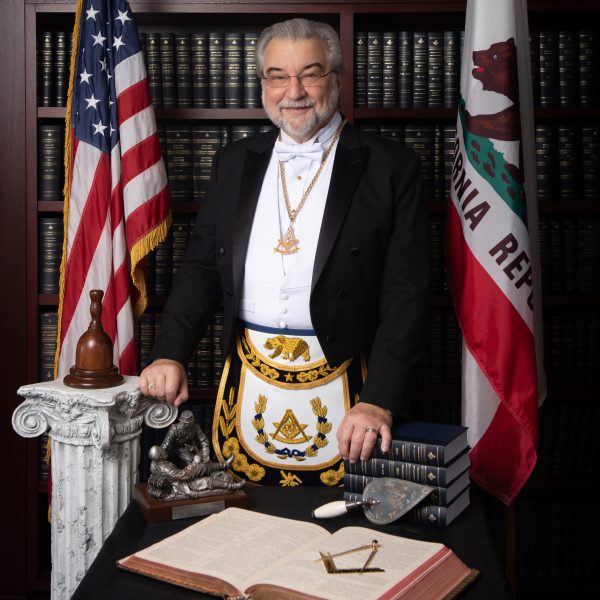

Meet Grand Master Randall Brill

Grand Master Randall Brill, of San Diego No. 35, explains his love of dolphins—and his vision for a Masonic fraternity in harmony.

On Sunday, October 23, Grand Master Randall Brill was installed as the highest Masonic officer in the state—the crowning achievement of a long career spent in Freemasonry. In addition to having served as master of his home lodge, San Diego No. 35, Grand Master Brill has also served on several Grand Lodge committees and boards, as well as on the Public Education Advisory Councils and as vice president of the California Masonic Foundation. And yet for all his work within the fraternity, Brill has also enjoyed a distinguished—and colorful—career outside of Masonry. For instance, he’s an expert dolphin trainer who helped study underwater sonar systems for the U.S. Navy, in addition to being an accomplished amateur magician. (Fittingly, he’s a charter member of Ye Olde Cup and Ball Lodge No. 880, a newly formed lodge that meets at the Magic Castle in Los Angeles.) Here, Grand Master Brill introduces himself and lays out his vision for the fraternity. (See Grand Master Brill’s 2023 proclamations here.)

How did you first come to Freemasonry?

I remember my father always really admired the Masons, and I guess that stuck with me. But I spent a lot of years thinking you had to be invited in, which isn’t true. When I moved to San Diego, I would pass every day in front of the Scottish Rite Center and think about it. Finally, I was at work one day and I saw a colleague wearing a square-and-compass ring, and I thought, That’s it. That’s a message. So I just stopped in one day and happened to find my lodge, San Diego No. 35.

What were you most surprised to learn about Freemasonry once you joined?

It was the sincerity. The lessons you draw from the ritual. The interactions with the other members of the lodge. My oldest son is now a past master back in Chicago, and when he was raised to the third degree, he said one of the reasons he wanted to become a Mason was that he had observed a change in me. He thought becoming a Mason had turned my personality around and made me a better person. That really touched my heart, and I knew where it came from.

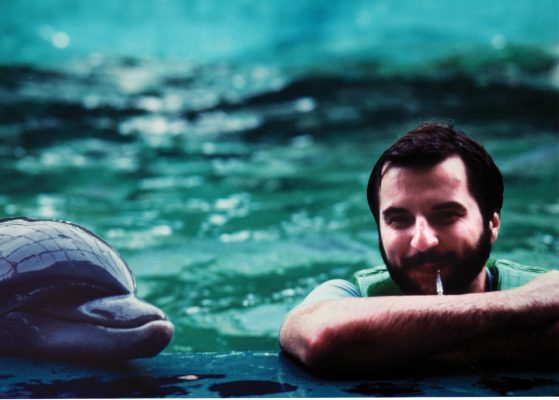

Can you tell us a little about your work? I understand you spent a lot of time training dolphins.

I was finishing my master’s in psychology, and my thesis had to do with studying group interactions with an Amazon River dolphin at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago. That really got me interested in the animals, so I went to the Brookfield Zoo because they had a group of performing bottle-nosed dolphins and I wanted to observe their interactions.. At the end of the summer, they had an opening for an attendant, and basically 20 years went by and I became the head trainer for the dolphin program. Then eventually I finished a Ph.D at Loyola University and was offered a job with the Naval Marine Mammal Program in Hawaii. I did another 20 years with the Navy and retired in 2009 and got a job as the general secretary for the Scottish Rite in San Diego, and did that for 10 years, and then retired again in 2019 and got tagged as the junior grand warden.

What exactly were you training dolphins for in the Navy?

What exactly were you training dolphins for in the Navy?

The fleet animals were used to detect swimmers and underwater mines. They’re very good at it because they have a natural sonar system that’s incomparable. Hell, they can find a quarter in a sandy beach as long as they know what to look for.

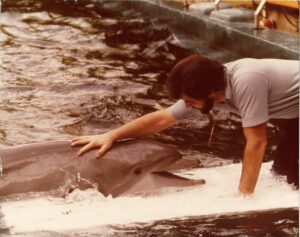

And I assume you came to really appreciate the animals.

Oh my God, they’re great. Dolphins don’t argue with you. They’re smart—just plain smart. No two are alike, and to work with them is a real experience. It opens your eyes in terms of inter-species relationships.

OK, back to Freemasonry. Your theme is “fulfilling our obligations.” What does that mean to you?

There are specific obligations I’m talking about. When a candidate kneels at the altar to take the degrees, he accepts a number of responsibilities, not the least of which is the philanthropic responsibility to support his brethren and their families. We’re also called to support public education. So those are my big drives: To reinforce and increase enthusiasm for those programs.

In addition, our long-range plan has a pillar called “diversity and harmony.” If your lodge is in a community of mixed ethnicity, does it reflect that? If not, why not? I think the lodge has a responsibility to allow itself to be attractive to everyone.

What would you like the fraternity to look like in 25 years?

I’d like to see a bigger mix of ethnicities represented to a significant degree. I want to see a real blend—a real brotherhood. Not just in pockets, but throughout the fraternity. Also—and someone might throw stones at me for saying this—I’d like to see the average age of membership come down, to where the average Mason is in his 30s or 20s when they’re coming in. We’re getting there by virtue of a couple of things. There’s an opportunity today to attract a younger body of membership. But they want to engage in different things: They want to get into the deep philosophical lessons and things of that nature, of which Masonry has plenty to offer. So our focuses are shifting, and that’s good.

—Interview by Ian A. Stewart

The following article appeared in the June/July 2010 issue of California Freemason magazine and is reprinted here with permission.

The Dolphin Whisperer

If someone told Randy Brill in 1975 that he’d end up training and studying dolphins for 34 years, he wouldn’t have believed it. At the time, his only experience with animals was in high school, when he led obedience training for German shepherds.

But he made a career out of it. Along the way, he confirmed a theory about how dolphins echolocate—and helped Navy engineers build better sonar. “It wasn’t a life goal, but it became a life’s passion,” says Brill, a past master of San Diego Lodge No. 35 and general secretary of the Scottish Rite there.

It all began with an Amazon River dolphin and Brill’s project for his master’s degree in psychology. He wanted to work on a large-brained mammal, but wasn’t keen on primates. Soon, he found himself using his behavioral psychology expertise to train bottlenose dolphins at the Brookfield Zoo near Chicago. Then he began a doctoral program in experimental psychology and started work on his mentor’s theory that dolphins “hear” through their lower jaws.

Dolphins find their way and locate objects in space by emitting high-pitched signals and waiting to hear how those sounds bounce back to them. But dolphins don’t have external ears.

So Brill set about testing the theory that dolphins “hear” by absorbing sound waves through their hollow, fat-filled lower jaws. He blindfolded a dolphin, Nemo, with soft rubber suction cups, then measured the dolphin’s ability to discriminate between targets with two different hoods over the lower jaw—one that blocked sound waves, one that didn’t. Nemo was 90 percent accurate with the hood that allowed sound to pass through to his lower jaw. But he could only guess when his jaw was covered by the hood that blocked sound.

Brill’s study changed the debate about echolocation. It also drew the attention of the U.S. Navy. The Navy’s engineers wanted to improve their sonar, and Brill came on board to test the engineers’ theories.

“The question when I got there was, ‘Could we build a system to literally replace the animal’s natural abilities?’” he says. “We’re not there yet, but we’re getting closer.”

That optimism and determination is what makes Brill tick—as a scientist and a Mason.

“The two statements I never like to hear are, ‘We did it once and it didn’t work,’ and ‘You can’t do that, it’s not possible,’” says Brill. “Well, we proved it is.” Brill concludes, “That’s the most salient connection between my work and Masonry: to approach things with an open mind.”